pressure in this space is figured by subtracting the

measured vacuum (10 in.Hg) from the nearly

perfect vacuum (29.92 in.Hg). The absolute

pressure then will be 19.92 or about 20 in.Hg

absolute. Note that the amount of pressure in a

space under vacuum can only be expressed in

terms of absolute pressure.

You may have noticed that sometimes we use

the letters psig to indicate gauge pressure and

other times we merely use psi. By common

convention, gauge pressure is always assumed

when pressure is given in pounds per square inch,

pounds per square foot, or similar units. The g

(for gauge) is added only when there is some

possibility of confusion. Absolute pressure, on the

other hand, is always expressed as pounds per

square inch absolute (psia), pounds per square

foot absolute (psfa), and so forth. It is always

necessary to establish clearly just what kind of

pressure we are talking about, unless this is very

clear from the nature of the discussion.

To this point, we have considered only the

most basic and most common units of measure-

ment. Remember that hundreds of other units can

be derived from these units; remember also that

specialized fields require specialized units of

measurement. Additional units of measurement

are introduced in appropriate places throughout

the remainder of this training manual. When you

have more complicated units of measurement, you

may find it helpful to review the basic informa-

tion given here first.

PRINCIPLES OF HYDRAULICS

The word hydraulics is derived from the Greek

word for water (hydor) plus the Greek word for

a reed instrument like an oboe (aulos). The term

hydraulics originally covered the study of the

physical behavior of water at rest and in motion.

However, the meaning of hydraulics has been

broadened to cover the physical behavior of all

liquids, including the oils that are used in modern

hydraulic systems. The foundation of modern

hydraulics began with the discovery of the

following law and principle:

. Pascal’s law—This law was discovered by

Blaise Pascal, a French philosopher and

mathematician who lived from 1623 to 1662 A.D.

His law, simply stated, is interpreted as pressure

exerted at any point upon an enclosed liquid is

transmitted undiminished in all directions.

Pascal’s law governs the BEHAVIOR of the static

factors concerning noncompressible fluids when

taken by themselves.

. Bernoulli’s principle—This principle was

discovered by Jacques (or Jakob) Bernoulli, a

Swiss philosopher and mathematician who lived

from 1654 to 1705 A.D. He worked extensively

with hydraulics and the pressure-temperature

relationship. Bernoulli’s principle governs the

RELATIONSHIP of the static and dynamic

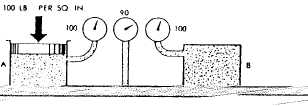

factors concerning noncompressible fluids. Figure

2-13 shows the effect of Bernoulli’s principle.

Chamber A is under pressure and is connected by

a tube to chamber B, also under pressure.

Chamber A is under static pressure of 100

psi. The pressure at some point, X, along the

connecting tube consists of a velocity pressure of

10 psi. This is exerted in a direction parallel to

the line of flow, Added is the unused static

pressure of 90 psi, which obeys Pascal’s law and

operates equally in all directions. As the fluid

enters chamber B from the constricted space, it

slows down. In so doing, its velocity head is

changed back to pressure head. The force required

to absorb the fluid’s inertia equals the force

required to start the fluid moving originally.

Therefore, the static pressure in chamber B is

again equal to that in chamber A. It was lower

at intermediate point X.

Figure 2-13 disregards friction, and it is not

encountered in actual practice. Force or head is

also required to overcome friction. But, unlike

inertia effect, this force cannot be recovered again

although the energy represented still exists

somewhere as heat. Therefore, in an actual system

the pressure in chamber B would be less than in

chamber A. This is a result of the pressure used

in overcoming friction along the way.

At all points in a system, the static pressure

is always the original static pressure LESS any

velocity head at the point in question. It is also

Figure 2-13.—Relationship of static and dynamic factors—

Bernoulli’s principle.

2-17